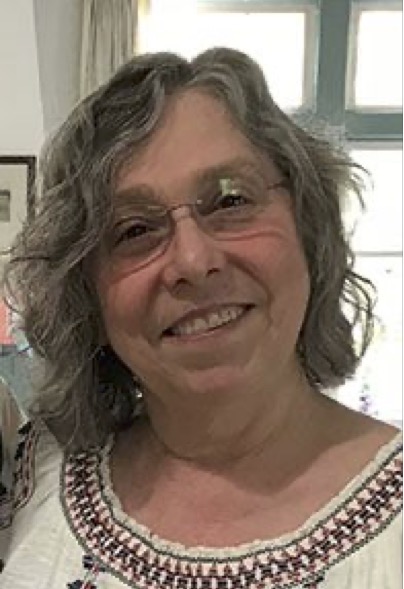

Pat is a professional writer, editor, and poet, who studied at the University of Iowa and moved to Portland, Oregon, with her best friend from college, a gay man eager to escape the Midwest and live fully out of the closet. Pat eventually cared for him and two other close friends who died of AIDS in the 80s and early 90s. This was her “found family”. Pat has written extensively about this experience, including a book-length series of poems, Love’s Gravity, which was a finalist in two small press competitions. Her chapbook, A Luminous Trail Through the Wilderness, was published by 26 Books/Unnum Press of Portland. Her writing has appeared in Calyx; the Oregonian; the Sun magazine; Fireweed: Poetry of Oregon; Talus and Scree; Broken Word: The Alberta Street Anthology and other publications.

Pat and her husband Alden Pritchett are currently involved in NE Village PDX, a grassroots nonprofit that helps residents of Northeast Portland age in their homes while remaining active in the community. One of her passions in life is social and economic justice. She also loves to sing.

Email Pat: pvivian3@comcast.net

Holding

Each time I visit Tom,

weeks have elapsed

since I last came,

and his body, his limits

are new again.

It takes a day

or so to figure out

how I fit in.

Just now,

I grasped his clammy hands

to help him up off the couch

so he could bask in the sun

by a window.

He used to not want me to pull,

just grab, stand firm

and let him hoist himself.

Now he cries out, “Pull!

Pull harder! It feels

like you’re going to let go.”

“I’m holding on to you

and I won’t let go,”

I promise him, “until you do.”

And I pull.

And I won’t.

Cruising the Loop

When we were living poor together

in that tall-windowed Lovejoy room,

we used to cruise the Loop, a cheap date

on a Friday night. We’d hop in the Toy and fly

above the wrinkled Willamette,

feel the wind tease the small red car.

We sped ahead through core Portland,

a flat stretch until the Marquam Bridge

swept us over the river like a mezzanine

high above the jazzy cityshine.

Of course

it was fleeting –

A few hurtling seconds and we’d drop

into a freeway trench, headed north again

past eyeless husks of warehouses

until the soaring Fremont ramp

sucked us up

into the cycle one more time:

Sometimes we slugged it out in campy lines

we knew by heart, love’s sleaze; or waltzed

in circles of felicitous wordplay; or froze

in queasy silence, both staring out the window.

And sometimes we veered perilously close

to whatever was actually happening

between us.

Tunnel Vision

(for Ronald Reagan)

Mr. President, this is war.

Twenty-five thousand were dead,

mostly young men

before you deigned to utter the A-word.

You need to know I’m losing a friend.

By sluggish degrees, the virus

is invading his brain.

The stellar glow that shined out of him,

that no scientist could possibly explain,

is contracting, growing more dense by the hour —

he’s becoming a white dwarf of a man.

We talk on the phone. He’s always home.

How are you doing? I ask gently, and he says

I love you

in answer to my question.

There are black holes in our conversation.

We say the same things again and again.

Old jokes like rituals, private one-liners:

I often, often, often repeat myself.

I almost always never contradict myself.

Do you have trouble making decisions?

Well, yes and no.

We talk about the weather –

a chilling fog grips the bay.

We talk about his mother –

there are things they can’t talk about

anymore. Like what? I ask

and he says, Viet Nam.

Mr. President, this is war.

But there’s a lighthouse beam

that pierces the fog in his brain,

and we invoke it each time

we talk on the phone. I say it to him.

He says it again. It’s the only defense we have:

I love you.

Universe

We spend days like this,

you stretched out on the couch,

me propped at the other end,

your feet in my lap, my hand

massaging in slow circles

or folded around your bony ankle.

Daffodils sprouting from a vase

are the loudest thing in the room,

yellow trumpets.

The TV coddles us in sterile, gauzy imagery.

It’s an anesthetic funnel, a leak

in the room where the color drains out,

your blue eyes going snowy at the edges

as you tell me,

“We’re as complex inside as the solar system.”

What will you stare into all day

if you can’t see?

When you hiccup and wince,

hiccup and cry out, I press my fingers

into your foot or cup your shin

to anchor you.

In the morning, you hover

on the edge of the bed, thin as a child’s

stick figure. I rub your shoulders, your hair;

when nothing human can touch

the chaos of a universe,

I bring morphine.

By midafternoon, you dress,

go downstairs to the garden,

squint up at the sun

and lie on the chaise lounge,

let me cover you.

Let us lie down together in the sun,

blinding and cruel

but warm.

Ask Nothing

Because each day brings us closer

to our undoing.

Because the knot of our lives will be torn

and soon.

It’s hard to be so far away

that when I reach out,

that clump of feathers

I know as my heart

flies out of its cage.

But it’s so easy

to leave the body

for only a moment,

asking nothing

but to be in the white room with you,

the bone-white room with the TV going.

Ask nothing.

Ask nothing of the body

that rises in its lightness

toward the stars.

Ask nothing of the stars,

who they are

how they got there.

Nothing of the breeze

that stops at your door.

Nothing of the trees

and their mirror images.

Nothing of roots

but to be roots,

and give thanks for the body,

this hollow landing in a wooden room.

Ask not why the limbs are so heavy.

These things are the body.

Descent (listen to a recording)

Suddenly it matters:

swifts headed to winter

brutality in Central America

twilight-dance in fall in Portland.

Pepper specks, a darkening vortex,

dusk cloud in spiral descent—

they pack into the gradeschool smokestack

like black smoke drawn back, more coming

with their impeccable timing—

miles of numinous blueblack cries chiming

overhead, thick as a galaxy.

They gather

without shoes or money,

like souls returning.

What passerine

passsion governs them:

who goes in first, who last; by what sign

are they called to their need

to commune; how they dive

through the vent without smashing

into ungiving stone. Do they see us,

a struggle of humans? Suddenly it matters:

they have sharp, strong claws

and are friendly to others

of their species—do they

believe in torture, God

or democracy? Or just

the good grit

of soot and seed.

Opera Singer at Golden Fields Manor

Her day-and-night attendant whisked her out

through an exotic, perfumed crack

of the authentic two-room suite.

Down the hall to dinner she rolled, eyes slack,

jaws dull—a plate placed

at the table, pale mannequin

fiddling with her napkin, hair swept up

smooth as a standing ovation,

nary a stray all the way to the crown.

Just then, she was queen of nothing.

Just as Joe Aikin’s spoonful of quaking Jell-O

found his left eyebrow, Elsie McCracken

raked wizened fingers down the window,

and Marge in her spidery hairnet

fended off a rattling dish tray spill,

Madame tall French knot made a pooched taut

O with ragged lips, as if surprised at herself,

and let loose a note that bloomed

whoopie into a gusty melody

whipping around the room. I swear

it carried the top of my head away, lifted the roof up

off all of us. Like raising the lid

and spotting a diamond

sparkling in a dumpster.

She might not know

who she’s been—duchess, diva, or vixen

trilling at Bayreuth, Covent Garden,

that starch-white wedding cake in Milan,

or why she’s here

at Golden Fields Manor—

but by Goddess, she can still sing.

Leading the Blind

The slender woman on the #12 bus

missed her cross-town connection and is lost.

Whitened knuckles of a solitary hand

clutching a white cane,

the other resting on the fur

of the panting canine, who is also lost,

she leans forward into an unmapped future

while the driver explores route options and calls Dispatch

to help reconnect her.

This lopsided 3-way intersection

is a six-pointed star, with such odd angles

it would be easy to get lost

at the corner of NE 57th, Alameda and Sandy.

Our bus slides to a halt,

doors open while the driver exits, offers his arm

and escorts the woman and her guide across the street,

waiting politely as they board the #71.

All of this, of course, takes a few minutes

and throws the bus off schedule,

leaving everyone else

behind, bound to their own connections.

But suddenly Now is something we have plenty of.

Here is what you need.

Time louvers its doors open wide and settles

with it’s old friend Being over the whole bus.

We are so ready for this, we are waiting

for the light to turn green,

we are waiting

for more drivers like this, we are ready

as he steps back up to his seat, to greet him

with a groundswell of clapping

that rises out of us like a hungry wave —

spontaneous combustion

as the bus lurches into motion

Revenge

Decades after her shaggy fling

hiked up the Big Apple skyline,

Fay Wray is back in town

stomping around in a pair of red stilettos,

come-hump-me pumps heroic as fire engines

each half a block long. Sporting a natty ensemble

cinched at the waist, straight out of “I Love Lucy”

she strides into six lanes, tall as an empire.

There will be no more art made of her

terrorized screams, no crowds stampeding

onscreen, no ripped diaphanous gown.

See how she unspools the film.

See her sweep airplanes out of the sky,

mop up trillions in third world debt

like soap scum, bleach mean CEOs

with Asset Clean, balance the federal budget

on one hand—while calmly with the other

she scoops up survivors from the collapsing tower,

cupping them safe in her palm.

See her shortstop the bombs.